Bethlehem – for more than two years, one of the world’s holiest churches has been undergoing restoration work. In this report, we would like to give a historical background about the wooden door and the mosaic covering the walls of the nave.

The wooden doors

From the humility door, heads of believers and visitors bow down in reverence to the child in the manger. Just in front of the door, we face tall wooden doors that separate the narthex and the nave, covered through the centuries by layers of dust and smoke coming up from oil lamps. Now, the restoration comes and reveals a corner worthy of contemplation and appreciation, which previously visitors used to overlook. The doors, which were built at the hands of two Armenian believers and then presented as a gift by the Armenian king Hethum I in 1227, were installed at the entrance of middle royal door. The doors were beautifully produced with crosses and other elements of ornamentation engraved on them, as well as inscriptions in Arabic and Armenian on the top part of them.

The Armenian inscription in English translation reads as follows:

“In the year 676, the door of the Holy Mother of God was accomplished by the efforts of Father Abraham and Father Arachel, at the time of the Armenian King Hithum the son of Constantine. May God have pity on the authors (of this work).”

While the Arabic inscription in English translation reads as follows:

“This door was completed with the help of Allah, may He be exalted, in the days of our lord, the sultan al-Malik al-Mu’azzam in the date of (the month of) Muharram the year 624(= Dec.1226-Jan.1227).”

It may seem, from the inscription, that al-Mu’azzam initiated the construction of the doors but it is most certain that the project had nothing to do with him and he was mentioned merely because he was the ruler at the time of the construction.

Mosaics

After passing through the wooden doors, one arrives in the nave of the basilica. Looking up at the walls, people can see a set of mosaic works on the upper northern and southern walls that date back to the 12th century.

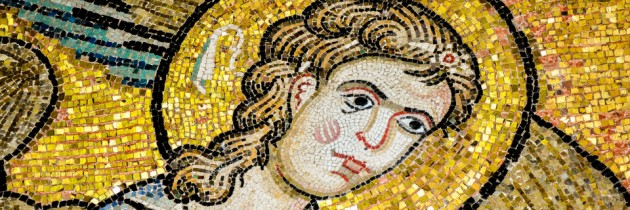

1) A set of 6 angels located between the windows with their face directed at the manger. Originally, there were 12 angels of which remained 7. Last March, a seventh angel was discovered behind a layer of plaster; restorers believe that it was covered for fear of destruction or falling-off. In 1169, the miniaturist Basilius Pictor created these works of art and his name appears on the third angel from the right on the northern wall.

The putting of the plaster of the 7th angel dates back to the 19th century where it was coated by a layer of ordinary paint.

Mosaicists at that time relied on the Byzantine technique of creating their works; three layers can be seen:

– The preparatory layer which was a foundation of stone.

– The mortar layer which resembles glue in its consistency. Mosaicists used to draw a sketch in colors where each color corresponds to a different type of tesserae (Latin for cubes or dice) which are pieces of stone, glass or metal (gold or silver) that have been cut in triangular or square shapes.

– The layer of tesserae.

A very innovative technique of applying tesserae in the upper walls of the nave was the tilting and setting gold and silver pieces at sharp angles. This procedure enhanced the reflection of light that is coming through the windows that separate the angels, and thus, increasing the amount of light that goes downward in the direction of visitors.

Over the centuries, many tesserae of the angel mosaics were lost. Therefore, restorers are filling in these lost parts with a layer that they engrave to give onlookers an idea of how they appeared before.

2) Mosaics in the middle part of the southern wall represent the names of Jesus’s ancestors according to the Gospel of St Luke (ch3: 23-38) while the mosaics in the middle part of the northern wall represent the genealogy of Jesus according to the Gospel of St Matthew (ch1: 1-7). Today, only seven of the ancestors can be seen with their names written in Latin.

Moreover, the southern and northern walls contain texts in Greek and Latin surrounded by geometrical shapes separated by acanthus leaves, candlesticks and incense burners. These texts represent decisions of the Ecumenical and local synods.

Saher Kawas

Read the complete article on en.lpj.org